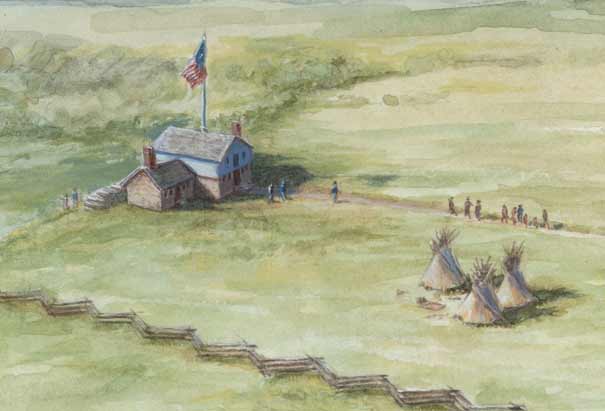

The US Indian Agency (1820-1853)

Along with building Fort Snelling at the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, the US government established the St. Peters Indian Agency on the military property. The agency was supervised by an Indian agent, a civilian appointed by the president of the United States to serve as an ambassador to Native American nations living in the region. Agents were responsible for being the eyes, ears, and mouth of the US Bureau of Indian Affairs to Native communities.

Indian agencies were created as part of the US government's efforts to control trade between the US and Native American nations. In 1806 the federal office of the Superintendent of Indian Trade was created to monitor and control economic activity between Native people and the US government. In March 1824 Secretary of War John C. Calhoun created the Bureau of Indian Affairs to replace the Indian Trade Office, officially placing responsibility for working with Native communities under the control of the US War Department. In addition to controlling trade, the bureau was responsible for settling disputes between Native Americans and European Americans, as well as for appropriating funds from Congress to fund efforts by the Indian agents to acculturate Native Americans into European American society.

Agents were ordered to report any violations of US trade and laws by European or US fur traders to the bureau's superintendents, local US military personnel, and to the US War Department. Agents were also responsible for resolving disputes between Natives and European American colonists within their jurisdictions, or any conflicts between different Native American nations, in order to prevent disruptions in the fur trade and ensure that US interests in their jurisdictions were not jeopardized. At the St. Peters agency, agent Lawrence Taliaferro worked frequently with both Dakota and Ojibwe communities to prevent conflicts and maintain peace in the region. Throughout its more than 30-year history, the St. Peters agency was administered by several individuals: Lawrence Taliaferro (1820–39), Amos Bruce (1840–48), Richard G. Murphy (1848–49), and Nathaniel McLean (1850–53).

During the early 1800s, the US government adopted policies aimed at acculturating and assimilating Native people into European American society. Agents at the St. Peters Agency encouraged Dakota people to give up hunting as a primary method of subsistence, educate their children according to European American standards, give up their traditional religion to become practicing Christians, and adopt European American agricultural methods. The agents also encouraged a change in traditional Dakota gender roles; traditionally, Dakota women and children had worked the fields and gardens, and the agents wanted men to give up hunting and take over this work. Agents as well as missionaries encouraged the Dakota to adopt farming on a larger scale so it could serve as the main form of subsistence for their communities, and to utilize European American cultivation methods (such as the use of plows drawn by draft animals).

The US government's policy of assimilation would effectively destroy the traditional cultural identities of Native American nations. Many historians have argued that the US government believed that if Native people did not adopt European American culture, they would become extinct as a people. This paternalistic attitude influenced interactions between Native Americans and the US government throughout the first half of the 1800s, and its effects continue to be felt today.

After the 1851 Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, many of Minnesota's Dakota communities moved to a reservation along the Minnesota River Valley. The US government determined that the St. Peters Agency was no longer needed, and it was soon replaced by two agencies on the new Dakota reservations: the Upper (Yellow Medicine) and Lower (Redwood) Sioux Agencies. By 1853 most of the Dakota living near the St. Peters Agency had moved to the new reservation, and the agency was closed down. Afterwards, many of the agency's buildings were used by private citizens.

Resources

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650–1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1984.

- Farber, Zac. "Taliaferro, Lawrence (1794‒1871)." MNopedia, February 11, 2019.

- M35, M35-A, P1203

Lawrence Taliaferro Papers, 1813–1868 (PDF)

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers relating to Taliaferro’s tenure as Indian Agent at St. Peters near Fort Snelling from 1820 to 1839. - Prucha, Frances Paul. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

- Prucha, Frances Paul. Documents of United States Indian Policy. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

- Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Abridged Ed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

- Sheehan, Bernard W. Seeds of Extinction: Jeffersonian Philanthropy and the American Indian. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1973.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Indian Agency Council House, 1835–37. Painting by David Geister, 2012. Source: Historic Fort Snelling collections.

Lawrence Taliaferro, United States Indian Agent at St. Peters, about 1830. Source: MNHS Collections.

Indian Agency Seal used by Lawrence Taliaferro, 1819–1839. Source: MNHS Collections.