The US-Dakota War of 1862

The causes of the US-Dakota War of 1862 were many and it remains one of the most important events in Minnesota history. The effects of the war can still be felt today. To learn more about the war itself, visit the US-Dakota War of 1862 website.

Fort Snelling played a central role in the war and its aftermath. In early August 1862, recruitment of the Sixth through Eleventh Infantry regiments meant for service in the Civil War had commenced. When news of Dakota attacks reached St. Paul, Governor Ramsey appointed Henry Sibley a colonel in the state's military forces and commander of the army that would march against the Dakota. Sibley led four hastily armed companies of the Sixth Infantry Regiment from Fort Snelling to St. Peter. Over the next few days, a trickle of supplies and detachments from the other partially recruited infantry regiments and militia units left Fort Snelling to join Sibley.

The state's military forces came under federal control on September 16, when Major General John Pope assumed command of the newly created Military Department of the Northwest. Sibley, just appointed a brigadier general of US Army volunteers, directed the US forces in the decisive Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, defeating the Dakota. Many of the Dakota combatants moved westward into Dakota Territory, while others went north to Canada, but many of the men who had fought stayed with their families, who could not move swiftly enough to escape. Numerous Dakota who had not participated in the war, as well as some who had, met Sibley's army at a place that came to be called Camp Release. When he arrived, Sibley took the Dakota into the custody of the US military.

Over the course of three weeks, a military commission tried 392 Dakota men for their participation in the war and sentenced 303 of them to death. Some of the trials lasted no longer than five minutes. At the time, and ever since, the legal authority of the commission and the procedures it followed have been questioned. After the trials, General Pope ordered that the convicted Dakota be removed to Mankato, and the Dakota non-combatants be removed to Fort Snelling. Sibley put Lieutenant Colonel William R. Marshall and 300 troops of the Eighth and Fifth Minnesota Infantry in charge of the forced removal of the Dakota from the Minnesota River Valley to Fort Snelling. The Dakota who traveled to Fort Snelling beginning November 7, 1862, numbered 1,658. The vast majority were children, women, and elderly.

The Fort Snelling Concentration Camp

The Dakota non-combatants arrived at Fort Snelling on November 13, 1862, and encamped on the bluff of the Minnesota River about a mile west of the fort. Shortly after, Marshall and his soldiers moved the Dakota to the river bottom directly below the fort. In December soldiers built a concentration camp, a wooden stockade more than 12 feet high enclosing an area of two or three acres, on the river bottom. More than 1,600 Dakota people were moved inside. A warehouse just outside the camp was used as a hospital and mission station. Throughout the camp's existence, soldiers of the Sixth, Seventh, and Tenth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiments guarded the stockade, controlling movement in and out. It is estimated that between 130 and 300 Dakota people died over the winter of 1862–63, mainly due to measles, other diseases, and harsh conditions.

The concentration camp at Fort Snelling was not a death camp, and Dakota people were not systematically exterminated there. The camp was, however, a part of the genocidal policies pursued against Indigenous people throughout the US. Colonists and soldiers hunted down and killed Dakota people, abused them physically and mentally, imprisoned them, and subjected them to a campaign calculated to make them stop being Dakota.

Removal of the Dakota and Ho-Chunk

On February 16, 1863, Congress passed an act that "abrogated and annulled" all treaties with the Dakota people. The act also stated that all lands held by the Dakota, and all annuities due to them, were forfeited to the US government. A second bill, providing for the removal of the Dakota from their ancestral homelands, passed on March 3, 1863. The aftermath of the US–Dakota War of 1862 also engulfed the Ho-Chunk, who were living at Blue Earth at the time of the war. The desire of colonists to remove all Indians from Minnesota led to a similar bill to evict the Ho-Chunk, who had been uninvolved in the war but resided on prime agricultural land that colonists wished to obtain.

In early May, the army put the Dakota captives from the Fort Snelling camp aboard steamers and took them to a desolate reservation at Crow Creek, Dakota Territory. The removal of the Ho-Chunk people coincided with that of the Dakota. For a brief time, the US army held hundreds of Ho-Chunk at Fort Snelling before they, too, were removed from the state.

Aftermath and the execution of Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan

After the US government forcibly removed the non-combatant Dakota from Minnesota, the war against the Dakota entered a second phase, and the concentration camp at Fort Snelling served a different purpose. In the summers of 1863–64, the US Army launched the Punitive Expeditions into Dakota Territory, intent on carrying war to the Dakota people. Fort Snelling became a center for marshalling supplies, stock, and troops for these efforts. From the spring of 1863 until the late summer of 1864, Dakota who had surrendered or been captured by the army were held at the Fort Snelling stockade before being exiled from Minnesota.

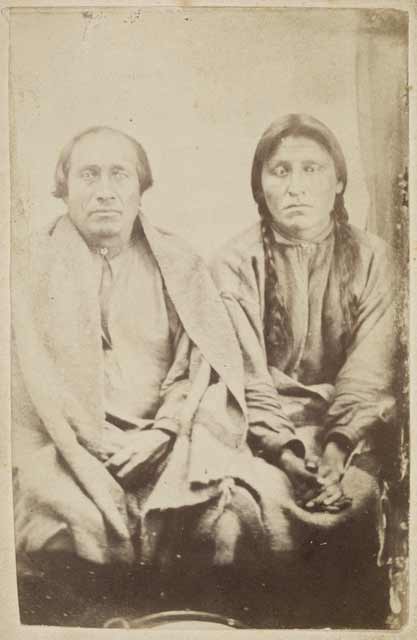

In November of the following year, an event marked the close of the US-Dakota War era at Fort Snelling. Bdewakantunwan (Mdewakanton) leaders Sakpedan (Little Six) and Wakan Ozanzan (Medicine Bottle), who had been involved in the war (though to what degree is still not certain), helped guide hundreds of Dakota people, including non-combatant women, children, and elderly, to safety in Canada after the fighting. US Army officers asked John H. McKenzie, who was then living near Fort Garry, Winnipeg if he would abduct the Dakota leaders and bring them across the border. McKenzie agreed to do so, enlisting a colleague named Onisine Giguere and others to help him capture Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan. McKenzie and his cohorts drugged the two Bdewakantunwan men using opiates, kidnapped them, and delivered them to the US Army at Pembina. The army then imprisoned them at Fort Snelling and tried them by military commission.

In separate trials, the military charged Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan with murder and general participation in "the murders massacres and other outrages committed by the Sioux Indians upon whites in 1862." Each charge included multiple specifications related to particular acts of violence. The commission made it clear within the specifications that they deemed the two men as having been "under the protection of the United States" when the war began, and that opposing US forces and the killing of US soldiers during the war were considered crimes.

Both Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan asked permission to obtain counsel. Permission was granted, but neither was able to secure an attorney. The two Bdewakantunwan leaders pleaded not guilty to all of the charges. In both trials, witnesses gave hearsay testimony, most of them claiming they had heard Sakpedan or Wakan Ozanzan talk about committing murders during the war. Multiple witnesses provided circumstantial evidence that Wakan Ozanzan participated in the violence. However, no person called to testify had personally witnessed Sakpedan or Wakan Ozanzan kill "white settlers" or US soldiers. Both defendants submitted final defense documents professing their innocence. Wakan Ozanzan was able to obtain the services of the attorneys Gorman and David in the writing of his final statement. In it, he argued that his abduction from Canada made his trial by US authorities invalid.

The commission found Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan guilty of both charges. Their executions were approved by Brigadier General Henry Sibley and President Andrew Johnson. The approval process took nearly a year during which time they were imprisoned at Fort Snelling. On November 11, 1865 the army hanged the Bdewakantunwan leaders outside the walls of the fort. In 1867 the Minnesota Legislature awarded McKenzie and Giguere $1,000 as payment for their services. While imprisoned, Sakpedan supposedly heard a steam engine pass by Fort Snelling and was quoted as saying, "'There—that is what has driven us away. That settles our fate! Over these lands my father was once undisputed chief, and over these hills I once rode free on my horse—but now,' taking up the chain 'look at this.'"

Resources

- Anderson, Gary Clayton, Woolworth, Alan R. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

- Bachman, Walt. Northern Slave, Black Dakota: The Life and Times of Joseph Godfrey. Bloomington, MN: Pond Dakota Press, 2013.

- Bakeman, Mary H., and Antona M. Richardson, eds. Trails of Tears: Minnesota's Dakota Indian Exile Begins. Roseville, MN: Prairie Echoes Press, Park Genealogical Books, 2008.

- Beck, Paul N. Columns of Vengeance: Soldiers, Sioux, and the Punitive Expeditions 1863–1864. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Canku, Clifford, Simon, Michael. The Dakota Prisoner of War Letters Dakota Kasapi Okicize Wowapi. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

- Carley, Kenneth. The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976.

- Cassady, Matthew and Peter J. DeCarlo. "Fort Snelling in the Civil and US–Dakota Wars, 1861–1866." MNopedia, November 23, 2015.

- DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

[Editor's note: The content for this webpage is largely derived from this work.] - Derounian-Stodola, Kathryn Zabelle. The War in Words: Reading the Dakota Conflict Through the Captivity Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2009.

- Gilman, Rhoda R. Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004.

- Hagerty, Silas. Dakota 38. Porter, ME: Smooth Feather Productions, 2012.

- Haymond, John A. The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law and the Judgment of History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2016.

- Isch, John. The Dakota Trials: The 1862-1864 Military Commission Trials: Including the Trial Transcripts and Commentary. New Ulm, MN: Brown County Historical Society, 2012.

- Lass, William E. "The Removal from Minnesota of the Sioux and Winnebago Indians." (PDF) Minnesota History 38, no. 8 (1963): 360–64.

- Millikan, William. "The Great Treasure of the Fort Snelling Prison Camp." (PDF) Minnesota History 62, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 4–17.

- Minnesota Historical Society. The US-Dakota War of 1862.

- Monjeau-Marz, Corrinne L. The Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. St. Paul, MN: Prairie Smoke Press, 2006.

- Monjeau-Marz, Corrinne L., and Stephen Osman. "What You May Not Know About the Fort Snelling Indian Camps." Minnesota's Heritage 7 (January 2013): 112–33.

- Osman, Stephen E. Fort Snelling and the Civil War. St. Paul, MN: Ramsey County Historical Society, 2017.

- Renville, Mary Butler, Carrie R. Zeman, and Kathryn Zabelle-Derounian-Stodola. A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity: Dispatches from the Dakota War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012.

- Twin Cities Public Television. The Past is Alive Within Us: The US-Dakota Conflict. [St. Paul, MN]: Twin Cities Public Television, [2013].

- "U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 : Overview," Minnesota Historical Society, https://libguides.mnhs.org/war1862.

- Vogel, Howard J. "Rethinking the Effect of the Abrogation of the Dakota Treaties and the Authority for the Removal of the Dakota People from Their Homeland." William Mitchell Law Review 39, no. 2 (2013): 538–81.

- Waziyatawin. What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press, 2008.

- Westerman, Gwen, and Bruce White. Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

- Wilson, Angela Cavender. "Grandmother to Granddaughter: Generations of Oral History in a Dakota Family." American Indian Quarterly 20, no. 1 (Winter 1996): 7–13.

- Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela, ed. In the Footsteps of Our Ancestors: The Dakota Commemorative Marches of the 21st Century. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press, 2006.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

The concentration camp, 1862 or 1863. Source: MNHS Collections.

A Dakota woman and her child in the concentration camp, 1862 or 1863. Source: MNHS Collections.

Apistoka at the concentration camp, 1862 or 1863. Source: MNHS Collections.

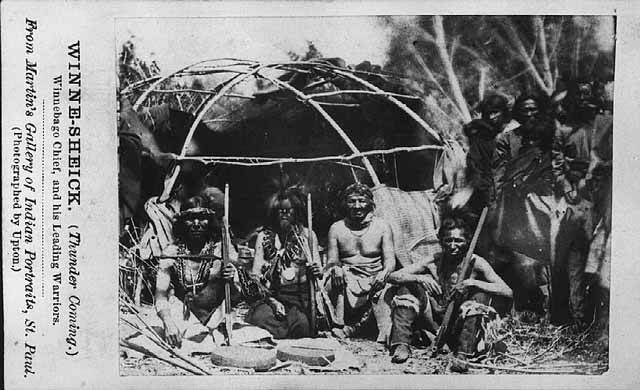

Winneshiek (second from left) and other Ho-Chunk leaders, likely at Fort Snelling, 1862 or 1863. Source: MNHS Collections.

Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan at Fort Snelling, 1864. Source: MNHS Collections.