Art and Architecture

From the stones of the building to the spaces indoors and out, the artwork and architecture of the Minnesota History Center are filled with symbolism that recognizes the stories and characters of the state.

Architecture

As a true Minnesota icon, the History Center was built from the resources found within the state. The building is constructed of granite from Rockville, travertine (limestone) from Winona, and a variety of luminous Minnesota hardwoods. Copper and Georgia marble contribute to the visual appeal.

Hammel, Green and Abrahamson of Minneapolis won a national design competition to become the building’s architects. BOR-SON/Knutson was the general contractor.

Percent for Art

The construction budget for the History Center included a “Percent for Art” appropriation. Minnesota Profiles is the third, and last, of the public art projects incorporated into the History Center. The others are Glass Etchings by Brit Bunkley (windows above the main doors and in the entry hallway) and the inlaid bronze Charm Bracelet sculpture (Great Hall Floor) by James Casebere. Percent for Art is administered by the Minnesota State Arts Board.

Minnesota Profiles

Brooks Family Courtyard

The courtyard art project captures the footprints of the old buildings and street that once extended to the grounds of the History Center, created by nationally recognized artist Andrew Leicester of Minneapolis. This sculptural group represents the former location of Summit Avenue with bench-height walls designed to depict the foundations of two apartment buildings that gave way to 1960s urban renewal. A series of terra cotta columns marks the edge of where Summit Avenue once crossed what is today’s History Center courtyard. Each column represents a different native Minnesota tree and features a three-dimensional silhouette portrait.

In October 1994, 140 volunteers sat for profile portraits and provided brief personal histories detailing their relationship to Minnesota. Leicester chose 37 profiles. These faces can be found in the 14 ceramic columns. Leicester spun the profiles into terra cotta and incorporated them into the columns. The artwork was unveiled Aug. 13, 1995, but the names of those chosen were not revealed. It will remain a mystery for those participants wondering if their faces inspired the artist.

Live trees provide shade, while the foundation of the sculptures can be used as a place for people to sit or take part in events.

Charm bracelet

Floor of Great Hall, Level 1

When artist James Casebere finished his work for the Minnesota Historical Society, the floor itself was a work of art. Ten images, representing Minnesota’s history and character, had been transformed into the components of a giant charm bracelet. But that bracelet isn’t whole; its shattered pieces appear to have fallen into the floor of the Great Hall. The charms were sculpted out of three-eighths-inch-thick bronze plates, then embedded in concrete. Terrazzo, a black, stone-like substance, was poured over the concrete, encasing the charms.

The charms and what they represent: tractor (agriculture); printer’s ink roller (communication and freedom of speech); tipi (Minnesota’s Native American population); mill (Minnesota’s lumbering and flour milling industries); house from Rondo Avenue (African Americans in Minnesota history); power plant (Prairie Island nuclear power plant on the Mississippi River); turtle (Ojibwe totem for medicine and healing); bear (Ojibwe totem for defense and warriors); fish (Ojibwe totem for learning and teachers); and whooping crane (Ojibwe totem for leadership and direction).

Some charms symbolize a sense of loss and irony. The ink roller can represent freedom of speech, or the lack of it. Two of the symbols, the house from Rondo and the power plant from Prairie Island, represent displaced people. St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood was home to a thriving African American community until the construction of Interstate 94 in the 1960s. And one of the last remaining populations of Dakota Indians in Minnesota lives on Prairie Island.

The four animal symbols are part of a group of five Ojibwe totems. The fifth totem symbolizes sustenance. In the bracelet it has been replaced by the tractor. The whooping crane, which was placed outside the charm, is an endangered species. The crane’s position in relation to the rest of the charms can be interpreted to mean that it is flying into the light of the Great Hall windows, or that it is flying out of the chain of Minnesota history. Casebere uses it as a metaphor for history in general.

Even the links are symbolic. Crooked linked lines, instead of a smooth circle, represent the chain. This symbolizes an Ojibwe ceremony that reminds participants of life’s temptations to stray from the straight path. Native American rock carvings and the concept of cyclical time also influenced the artist.

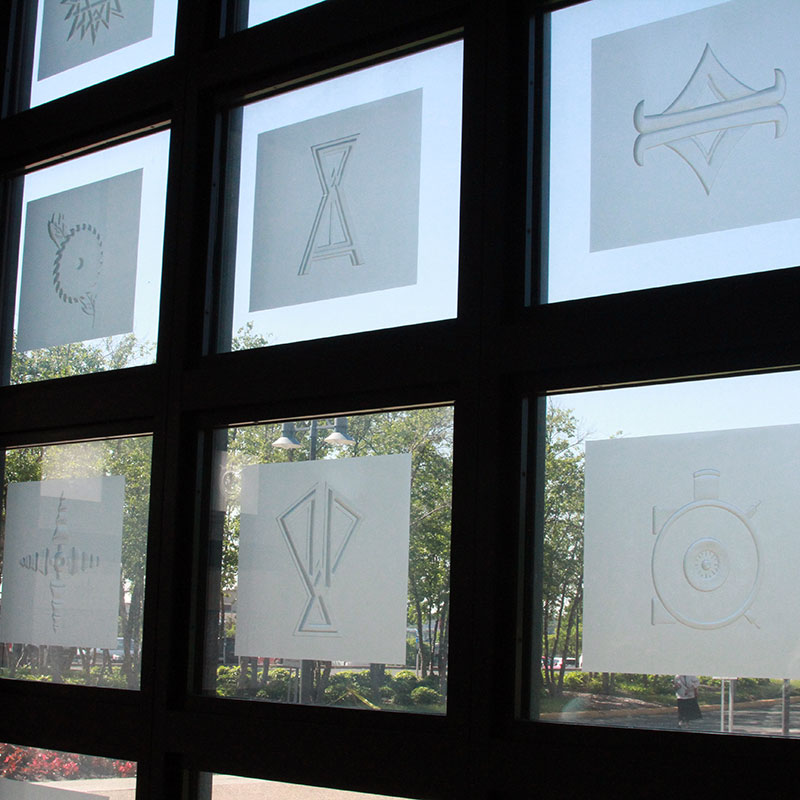

Glass etchings

Above entrances

Beautiful glass etchings can be spotted above the John Ireland and Kellogg Boulevard entrances and the courtyard doors. These geometric sandblasted panels, created by Brit Bunkley, complement the building’s classic architecture. The panels indirectly refer to Minnesota’s past, culture, and geography. He designed the images to be open to multiple interpretations. For example, one etching combines images of grain elevators and printed circuits, representing both agriculture and high technology industry.

Star motif

Throughout the building

An eight-pointed star can be seen in the ceiling of the Great Hall and throughout the building. Each pair of points represents the letter M for Minnesota. The star stands for Minnesota, the North Star State. The state was the northernmost state until Alaska joined the union.